Authors' suit charges racial bias in history book

By CHAT BLAKEMAN Clarion-Ledger Staff Writer

Tue, August 29, 1979

Is a ninth-grade classroom the place where Mississippians should learn that there have been more lynchings in their state than in any other? Will a photograph of white policemen arresting black demonstrators stir racial hatred or lead students to a true understanding of their past? These types of questions are at the heart of a battle that began Monday in U.S. District Court in Greenville before Judge Orma Smith. Although the issue is alleged racism in Mississippi schools, the, topic is not unequal facilities, alleged physical abuse, private academies or busing. The topic is a pair of books. The suit is being brought by a group that includes Millsaps College history professor Charles Sal-las and former Tougaloo College professor James Loewen, joint editors of a textbook on Mississippi history rejected by the State Textbook Purchasing Board in 1974.

The text, "Mississippi: Conflict and Change," presents what the authors contend is a candid but accurate picture of state history. It details subjects such as the treatment of slaves, blacks' accomplishments during Reconstruction, their plight in the years that followed and the sharecropper system that kept many Mississippians in virtual economic bondage. The authors charge that the Textbook Purchasing Board's rejection of "Conflict and Change" and approval of "Your Mississippi," the text now used, constituted pro-white bias in favor of texts that "minimize and denigrate the roles of black people in American and Mississippi history." The suit alleges, moreover, that the system by which the state approves school texts "is and has been an instrument of state propaganda to exclude controversial viewpoints, operates as a state instrument of unconstitutional state censorship, and fails to provide due process of law." Joined by representatives of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Jackson, the Jefferson County School Board and others, the authors ask that the court order "Conflict and Change" added to the list of approved texts and decide whether the book adoption system is valid. The board chooses books based on the recommendation of a rating committee and can approve as many as five books in each category. Acceptance of one text does not require rejection of others.

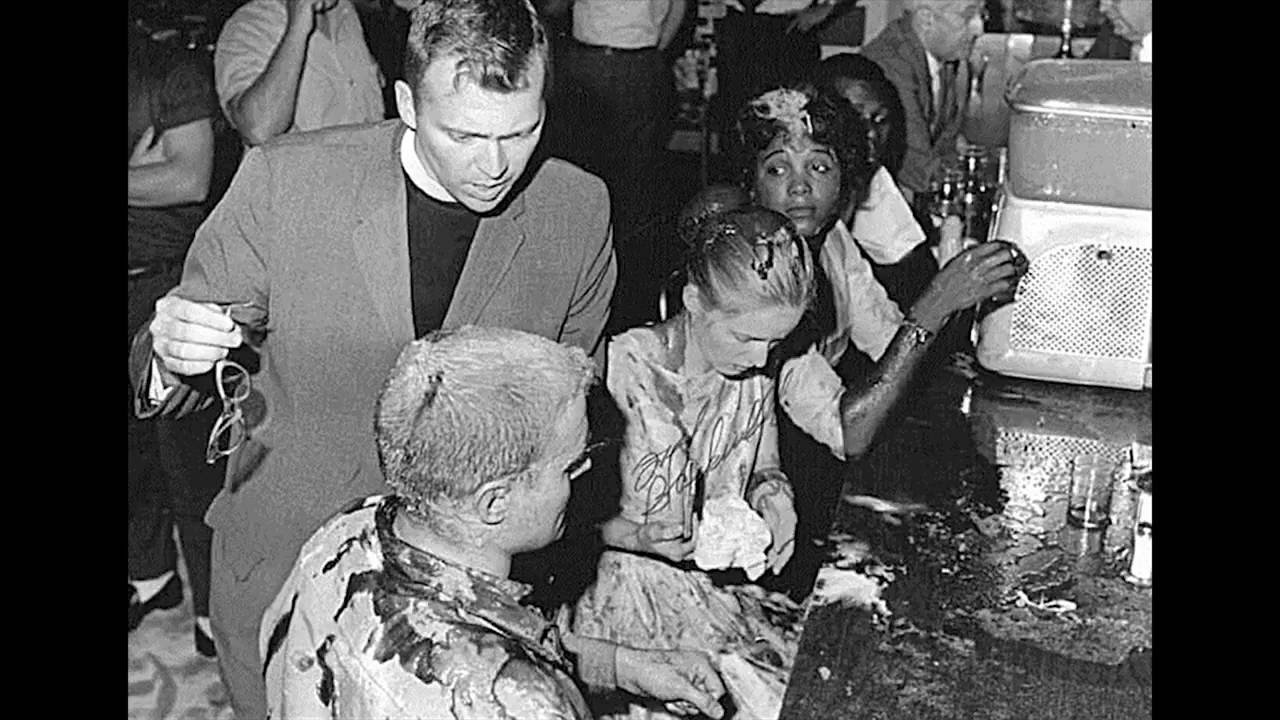

Although the rating committee rejected "Conflict and Change" on a 5-2 vote (five white members voted against the book and two blacks for it), the state maintains race was not a factor in the decision. The action, the state contends, was based on "racially neutral educational and academic standards." In statements made for the court, and in the ratings made in 1974, board members said that "Conflict and Change" did not include a teacher's manual when it was submitted for approval, employed a vocabulary too advanced for the average Mississippi ninth-grader and did not give "proper emphasis to the economic, social and spiritual development" of Mississippians. Others cited as offensive a photograph in "Conflict and Change" showing the remains of a black man who had been lynched and burned. Gathered around the bonfire is a crowd of whites. "I feel that this book contains too many controversial issues to fit properly into the curriculum of the schools of Mississippi," wrote committee member Harold E. Railes in his evaluation written in 1974. Another member called the book "too racially oriented." Frank Parker, the attorney representing the "Conflict and Change" group, maintains that race and controversy are the real reasons behind the committee's action. The other reasons are "rationalizations after the fact," Parker contends. ."There have been more lynchings in Mississippi than in any other state and you can't ignore that," Parker said. "Your Mississippi" was written by historian John K.Bettersworth, who retired last year as academic vice president of Mississippi State University. In its latest revisions, the book has been used in state schools since 1968 for required ninth-grade state history courses. In an attempt to show that "Conflict and Change" is the better book, the suit challenges the history presented in "Your Mississippi," citing among other examples: That it devotes only four paragraphs to the treatment of slaves and that those passages "minimize the brutality of the system and accentuate mitigating factors." For example, the suit cites Bettersworth's statement that "some slaves who were house servants received an education" and notes the book fails to mention the prohibitions against educating slaves and only 5 percent of the slaves were domestics. That In summing up the modern civil rights era, Bettersworth recounts that, "Gradually Mississippians, black and white, found they could get along together as they always had," without discussing adequately the reasons behind the civil rights movements. That in its use of photographs, the book discriminates against blacks.

"Your Mississippi" has only three photographs or 5 percent showing blacks only, while "Conflict and Change" has 20 or 25.6 percent. Bettersworth, a historian best known for his research into Mississippi society during the Civil War, dismisses the criticism, saying his book does not distort the role of blacks. Mississippi's system of adopting textbooks is shared in some form by roughly half the 50 states and most southern states. The system, provides textbooks free to public and parochial school students. Individual school boards may use whatever texts they want, but only those on the state's list can be purchased with state funds.

In practice, choices are limited to books on the list, which is revised every six years. The suit involving "Your Mississippi" and "Conflict and Change" is expected to last several weeks and it may be several months before the court renders a decision, lawyers for both sides said. Here are examples of disparities between the textbooks "Your Mississippi" and "Mississippi: Conflict and Change": ON SLAVERY Your Mississippi "While there were a number of cases of cruelty to slaves, public opinion and state law tried to see that the slaves were not mistreated. Plantation owners cautioned their overseers against using brutal practices, but overseers were noted for cruelty The code (of 1832) required the master to keep all of his slaves in good health and physical well-being from the cradle to the grave. In general, slaves were treated well or badly on the basis of how good or bad their owners were." Conflict and Change: "When the slaveowner or overseer felt that a slave had done wrong, he sometimes punished the offender severely . . .

One slave recalled a whipping that he had witnessed: 'I saw Old Master get mad at Truman, and he buckled him down across a barrel and whipped him till he cut the blood out of him, and then he rubbed salt and pepper in the raw places.' . . .This harsh treatment had other aims... it made them fear white men, and it attempted to make them feel that whites were 'naturally' superior to blacks." ON RECONSTRUCTION Your Mississippi: By 1874, taxpayers were ready to revolt. ..

Vicksburg and Warren County were scenes of the first incidents. Most of the city and county offices were held by blacks. Since whites paid ninety-nine percent of the taxes, they were very unhappy. The city and county debt, which had been only thirteen thousand dollars in 1869, had climbed to $1.4 million for Vicksburg alone by 1874 .

After 1875 the old hatreds began to fade. Mississippi was back under the control of native whites." Conflict and Change: "Many Mississippians still believe the 'myth of Reconstruction,' that the period directly after the Civil War was a time of bad government, 'Negro domination,' and racial tension. We now know that most of this myth is not true Many of the black leaders in Mississippi were educated; several were college graduates. Those who were honest and able were usually supported by both black and white voters.

All they asked was equal rights before the law. On the whole, Mississippi was especially fortunate in having capable black leaders during these years." ..,...:'.;

ON THE '60s , " Your Mississippi- "The 1960s were years of crisis. A showdown over desegregation and civil rights occurred. As a result, Mississippi's relationships with the national government were strained. After the Supreme Court's desegregation decision of 1954, Mississippians took vigorous measures to resist. One of those was the organization of a group known as the White Citizens' Council." Conflict and Change: "In 1954, the Supreme Court finally ruled school desegregation illegal. A few white people agreed with the decision but did not speak out effectively. Others organized the Citizens' Councils and passed new laws to resist integration. At the same time, a few black people began to express their dissatisfaction with segregation.".

ON THE MISSISSIPPI SOVEREIGNTY COMMISSION Your Mississippi "In 1956 a State Sovereignty Commission was set up to take the Mississippi case to the rest of the country." . Conflict and Change: "One of the most important acts passed in 1956 established a State Sovereignty Commission to preserve segregation. The commission promptly hired secret investigators to inquire into 'subversive activities' ... The commission also operated a public relations department to publicize to the nation the benefits of Mississippi's segregated way of life."