Mississippi never leads nor follows. It intensifies whatever fears and prejudices are already present in the larger society as if to say, "We can do it too," worried that, if we don't, we might be overlooked or forgotten about.

"Do you hate blacks and queers? We really, really hate them. We'll prove it, and boy, will you be impressed. Do you want to stop abortion? We really want to stop abortion. We'll do anything to stop it. Boy, will you be impressed!"

It's not that we can't change, or be loving, or human. We once tried to kill James Meridith, but now he walks those same streets as a hero. People ask him to pose for a photo with their children. It's almost as if we proved our point about integration; now, we can go back to being human again. We never really hated the guy; we were just trying to show how dedicated we were to this idea, even though those who did lead were leading the entire country in another direction.

Maybe, ultimately, it's a matter of confidence. Maybe if we had more of it, we wouldn't be so determined to lead the way on the most prevalent negative emotions. Maybe then we could say, "That's too much. We don't want any part of that."

Yesterday we had a lecture from Donna Ladd, formerly the founder of the Jackson Free Press and now Editor of the Mississippi Free Press. When I first started blogging, some of the people who now run very political blogs recognized me as having once been very political and tried to win me to their side by impressing me with how much they hated and disagreed with Donna. Now that the face of journalism is changing, I worry that those same guys are having a much larger impact than they deserve. That's not to say we didn't suffer from horribly biased news before, but for a while, we had almost liberated ourselves from that.

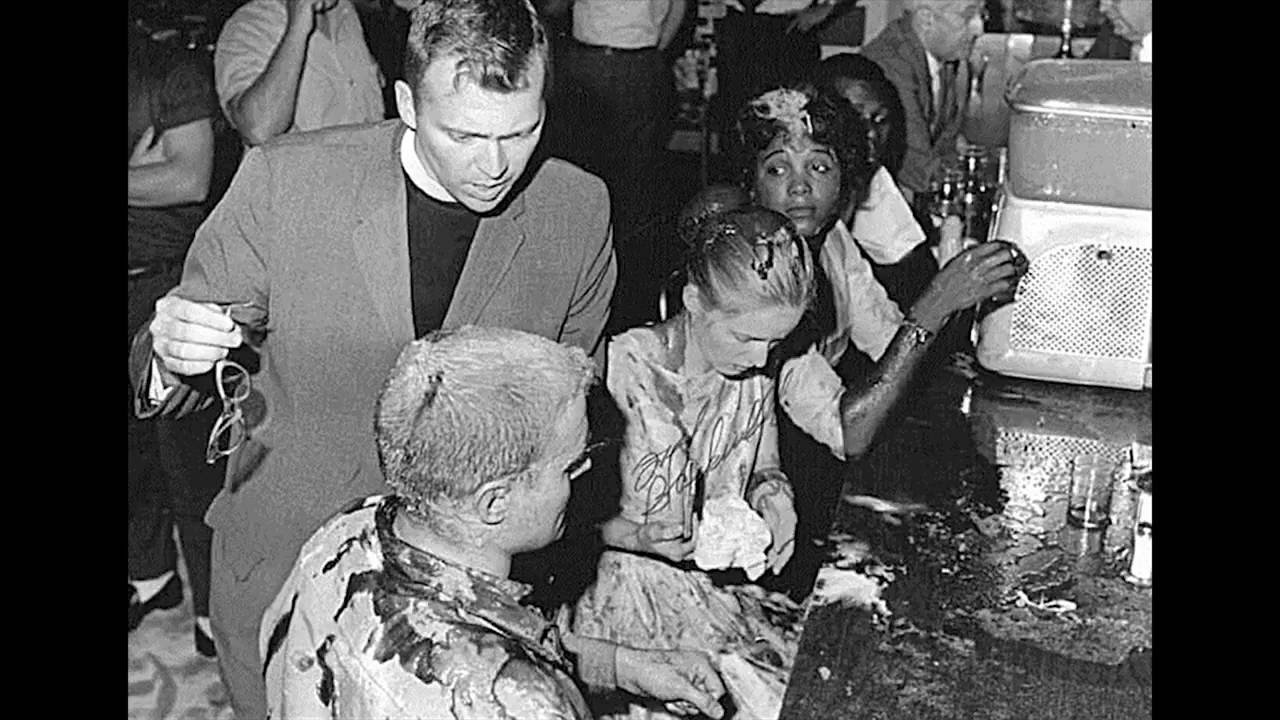

Donna has launched more young writers than I've even met. That makes her the perfect addition to the McMullan Young Writers program. Donna's from Philadelphia, Mississippi. She's just a couple years older than I am, and I was born in 1963. If you think about what happened in Philadelphia in 1964, then you can't really blame her for feeling some sorta way about Mississippi.

Those feelings made her want, more than anything, to escape Mississippi and never come back. I know of a lot of people who had the same feeling, some really famous ones like Oprah Winfrey and Leontine Price, and Tennessee Williams. Williams didn't go far, but in the 50s and 60s, New Orleans was an oasis of its own. There were only a few places in the country where he could be what he was, New Orleans was one, and Mississippi was not.

At one point in her lecture, Donna asked the question that I spend a great deal of time thinking about. "How many of you want to leave Mississippi when you graduate?" More than half of the hands went up. Some with energy and enthusiasm.

I talk about this with my friends a lot. "How do you keep your children here?" So many of my generation face this. Some of the young people in the forum that day were actually children of people I've known for a long time, raising their hands to say they want to leave Mississippi--to my mind, they want to leave those who love them more than anything. I can't really blame them. We invest so much treasure and time and energy and blood into raising these children, working so very hard to make sure they become remarkable people, and when they do actually become remarkable people, can we really ask them to stay here knowing that they might have to clip the wings we spent a lifetime giving them?

So much of what happened in Philadelphia that summer in 1964 touched my life. Even though I was just learning to walk, it was so close to me. My father always told the story of how the FBI called and wanted forty desk sets in forty-eight hours and how he struggled to fill the order. Ben Puckett talked about the day the FBI called to rent equipment to dig up an earthen dam. Clay Lee was a passionate young minister who the conference moved away from some pretty terrible things in Jackson, at Galloway, and sent him to a quiet country church where the troubles of Mississippi wouldn't upset his promising career, and they sent him to--Philadelphia Mississippi, just months before June of 1964.

I can't really blame Donna for leaving Mississippi. We didn't exactly lay an appetizing table before her. It's a miracle we ever got her back.

When I was at St. Catherine's, I would have coffee with some guys, and one of them told the story of how they longed to leave Mississippi and see the world, and did, but when he saw in the newspapers that Rabbi Nussbaum's office and synagog were bombed, he figured he needed to go back to Mississippi. He never hated Mississippi, but he never thought he'd get such a loud call to come back to her, either.

Many of Faulkner's characters spend a great deal of time turning over in their head what it means to be from Mississippi. In Absalom, Absalom! my sometimes favorite novel, Quentin Compson struggles with his feelings about his home. Throughout Faulkner's books, the Compsons often represent the moral heart of Mississippi. Far from home, he says, “I dont hate it he thought, panting in the cold air, the iron New England dark; I dont. I dont! I dont hate it! I dont hate it!” I've never really had a Quentin Compson moment, but it's been close. I've known a lot of people who did, though, and acted on it. It's our own fault, really. Everybody has a chance to make it better, but not everybody does.